1. Introduction

2. Sleep current in practice

2.1. Measuring tool

2.2. Understanding sleep currents correctly

3. Conclusion

1. Introduction

In IoT systems and battery-powered devices, microcontrollers spend most of their time in a dormant state, so sleep current – the current consumed when the system is “sleeping” – often has a much greater impact than the current consumed when operating. Especially with applications like BLE beacons, sensor nodes, or wearables, devices can sleep for over 99% of their operating time, meaning even a few microampere differences in sleep current can significantly alter battery life from a few months to several years. Nordic Semiconductor’s nRF52840 is known as a BLE SoC with very low power consumption, with sleep current values in the microampere range as stated in its datasheet. However, in practice, many projects have reported much higher current consumption than expected, even reaching hundreds of microampere or several milliampere values despite the firmware putting the system to sleep. The main reason is that CPU-level sleep is not synonymous with system-level sleep: clocks, peripherals, BLE radios, GPIOs, or external hardware components can still run in the background and continuously wake the SoC. Furthermore, datasheets often reflect ideal measurement conditions, while the actual system is a combination of firmware, BLE configuration, hardware, and measurement methods. This article aims to clarify the nature of sleep current on the nRF52840, highlight the differences between theory and actual measurements, and provide a systematic approach to analyzing, measuring, and optimizing current consumption down to the microampere level in practical applications.

2. Sleep current in practice

2.1. Measuring tools

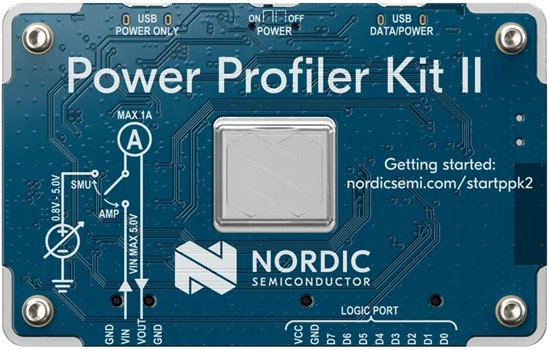

Nordic Semiconductor’s Power Profiler Kit II (PPK2) is an affordable hardware and software tool that helps engineers flexibly measure power consumption for IoT devices, especially with the Nordic nRF chip, allowing simultaneous viewing of both average and high-current event data with a faster sampling rate (100ksps), integrated via the nRF Connect application on a PC for more efficient energy analysis and optimization.

The Power Profiler Kit II (PPK2) is a specialized power consumption measurement tool developed by Nordic Semiconductor, designed for energy analysis and optimization in low-power embedded systems. This device provides high-accuracy current measurement capabilities, particularly suitable for battery-powered IoT applications.

Key features of the PPK2 include:

- Flexible current measurement, supporting both average current and peak current modes, allowing for detailed analysis of system power consumption behavior.

- High sampling rate, up to 100 kSamples/s, approximately 10 times faster than the previous generation, enabling clear observation of very short power consumption events such as radio on/off, wake-up, or interrupt handling.

- The included software, integrated into the nRF Connect for Desktop Power Profiler application, allows for visual real-time display of measurement data and supports data export for further analysis.

- A 10-pin logic interface allows monitoring logic signals from the test device (DUT) synchronized with current consumption data, useful for linking firmware behavior to current spikes during energy optimization.

- The PPK2 has a wide range of applications, particularly effective in optimizing energy consumption for BLE, LTE-M, and NB-IoT devices, and is often used with development kits such as the nRF9160.

The basic operating principle of the PPK2 is quite simple: the device is connected to a computer via a Micro-USB cable and to the DUT using jumper wires to both power and measure current consumption. Users utilize the nRF Connect Power Profiler application on their PC to configure the measurement mode, observe the current graph over time, and thus detect periods of high or low energy consumption in the system’s operating cycle.

The target users of the PPK2 are primarily hardware and software engineers developing battery-powered IoT products, as well as those who need to analyze and optimize battery life for low-power applications where every microampere counts.

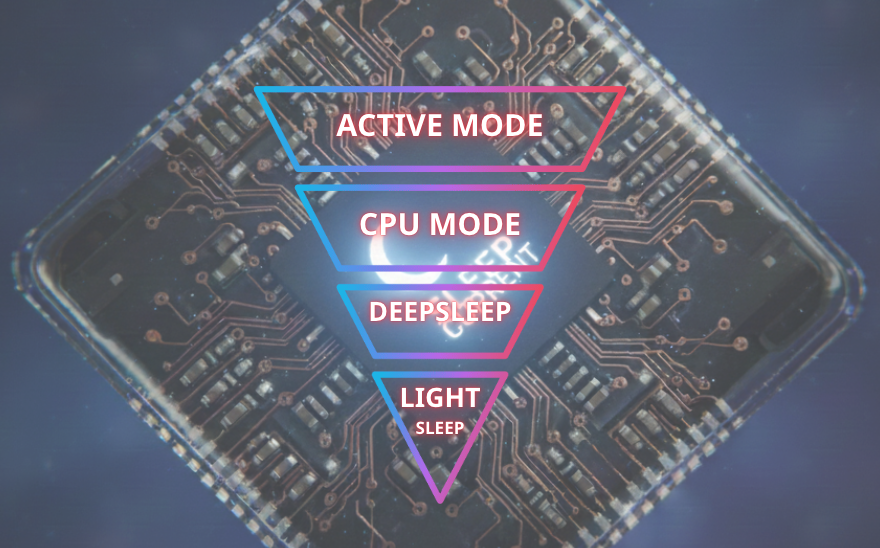

2.2. Understanding sleep currents correctly

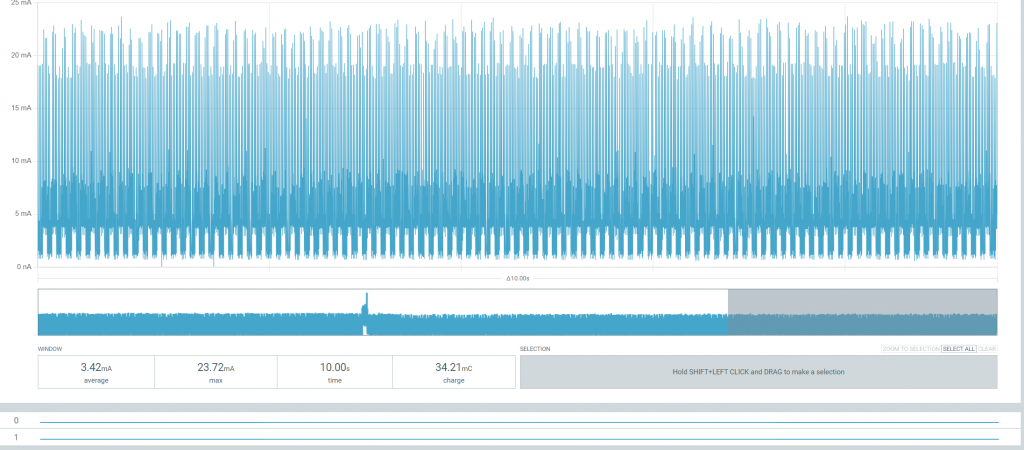

To clarify the information related to Sleep Current, we measured the nRF52840 using the Nordic Power Profiler Kit II (PPK2) at a sampling rate of 100 kS/s over a period of 10 seconds, yielding the following results:

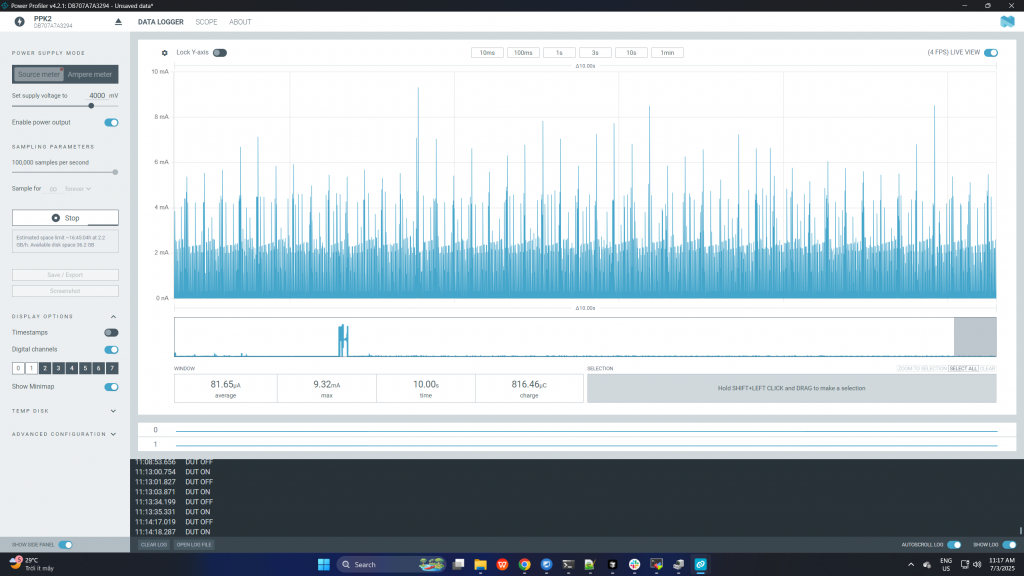

Overall view: “The device is not really sleeping”

Observation shows that the current fluctuates continuously from ~0 mA to ~20+ mA, with no “flat” segment at the µA level; the pulse density is high, uniform, and repeats periodically. This is not true sleep, but rather a CPU sleep mode while the radio/clock/background tasks are still running. This indicates that the device is being woken up periodically; even though the firmware has invoked sleep, the current consumption still varies significantly with mA‑level spikes. This proves that ‘sleep’ at the CPU level does not equate to low power at the system level.

For this case, the “thought it was sleeping” case: the average is low but the underlying behavior is still wrong. It’s easy to see that the measured parameters include: average current: ~81.65 µA, peak: ~9.32 mA, Measurement time: 10 s, charge: ~816 µC. Next, looking at the waveform, the baseline is quite low (µA–tens of µA) but there are still mA-level spikes appearing continuously and there is no stable flat-line segment. The device has not really entered a proper System ON low-power mode; the BLE radio or timer is still active, and the sleep current does not reach the datasheet level. Although the average current is only about 80 µA, the waveform shows that the device is still generating periodic mA-level spikes. This is a common mistake: evaluating sleep current only based on the average value while ignoring the actual behavior of the system.

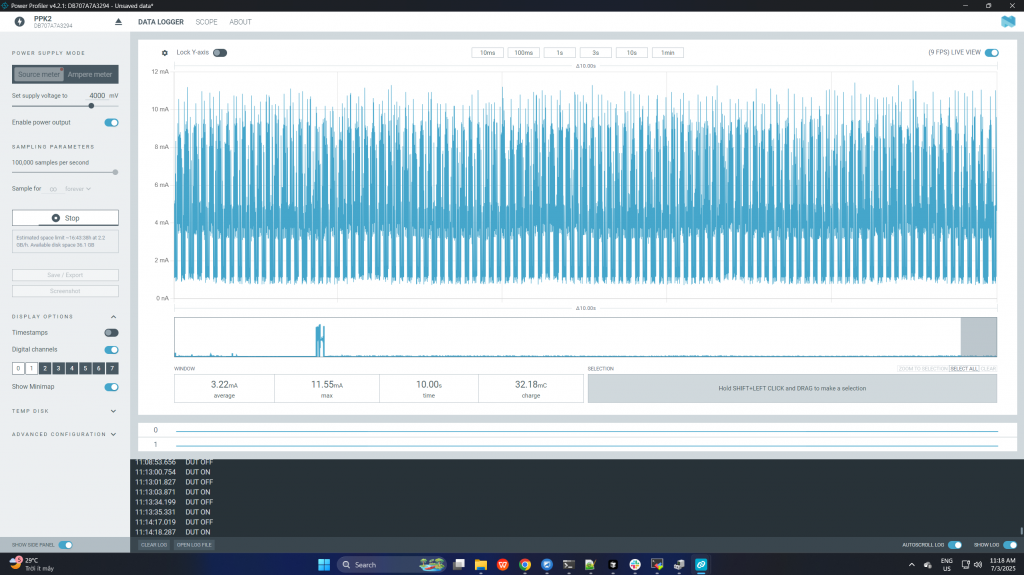

Finally, let’s look at this figure: the Active / BLE-heavy state (reference) with parameters: average: ~3.22 mA, peak: ~11.55 mA, charge: ~32.18 mC / 10 s. This corresponds to a state of dense BLE advertising or a short BLE connection interval, where the CPU + radio are operating frequently, showing the current consumption when the device is actively running. Notably, the waveform of the “non-optimized sleep” state (previous picture) has a shape very similar to this active state.

3. Conclusion

Sleep current is often treated as a single number quoted from a datasheet, but practical measurements on the nRF52840 show that it is a system-level characteristic, not merely a CPU state. Through real measurements using the Nordic Power Profiler Kit II (PPK2), this article demonstrates that a device can appear to be “sleeping” at the firmware level while still consuming significant energy due to periodic wake-ups, active clocks, BLE radio activity, or misconfigured peripherals.

The measurement results clearly show three distinct behaviors: a fully active BLE-heavy state with continuous milliampere-level current, a misleading “average-low-current” state where the baseline is low but frequent mA-level spikes persist, and a properly optimized sleep configuration where the system finally approaches the microampere-level currents stated in the datasheet. This highlights a common pitfall in low-power design: relying solely on average current values without examining the actual current waveform can lead to incorrect conclusions about battery life.

Using a high-resolution measurement tool such as PPK2 is therefore essential. Its high sampling rate makes short current spikes visible, enabling engineers to correlate power consumption with firmware behavior and identify hidden wake-up sources. Only by analyzing both the shape of the current waveform and the statistical values (average, peak, and charge) can true low-power operation be verified.

In conclusion, achieving datasheet-level sleep current on the nRF52840 requires a holistic approach that combines correct firmware sleep states, careful BLE configuration, proper clock and peripheral management, and clean hardware design. When these factors are addressed together—and validated with accurate measurement tools—microampere-level sleep current is not only theoretical but achievable in real-world IoT applications.