Edge AI for Predictive Maintenance: Unsupervised Vibration Anomaly Detection on MAX78000

1. AI Capability of ThingIQ

2. Data Acquisition and Signal Preprocessing

2.1. Vibration Sensor Overview

2.2. Signal sampling

2.3. FFT – Based Feature Extraction

3. AI Model Architecture

3.1. Model Tensor Description

3.2. Training

4. Deployment on MAX78000

5. Conclusion

1. Al Capability of ThingIQ

In modern industrial IoT systems, sensor data—particularly vibration data—plays a critical role in assessing equipment health. However, traditional monitoring approaches based on fixed thresholds are often inadequate in complex operating environments, where load conditions, rotational speeds, and environmental factors continuously vary.

ThingIQ leverages Artificial Intelligence (AI) as a core intelligence layer within its IoT platform, enabling early anomaly detection and predictive maintenance directly at the edge device, with low latency and high energy efficiency. Building on this foundation, ThingIQ adopts an AI-first approach, in which machine learning models are embedded directly into the IoT data processing pipeline. Rather than merely collecting and visualizing sensor data, the platform focuses on analysis, learning, and inference from real-time sensor streams.

This approach is particularly well suited for large-scale industrial and IoT systems, where operational requirements include:

- Early anomaly detection;

- Low-latency response;

- Reduced reliance on cloud-based inference;

- Optimized energy consumption.

To enable reliable and data-driven intelligence, the effectiveness of AI models fundamentally depends on the quality and structure of input data. In industrial environments, raw sensor signals are often noisy, non-stationary, and highly dependent on operating conditions. Therefore, a robust data acquisition and signal preprocessing pipeline is a critical prerequisite for meaningful learning and inference. The following section describes how vibration signals are acquired and transformed through signal preprocessing techniques to extract informative representations for subsequent AI-based analysis.

2. Data Acquisition and Signal Preprocessing

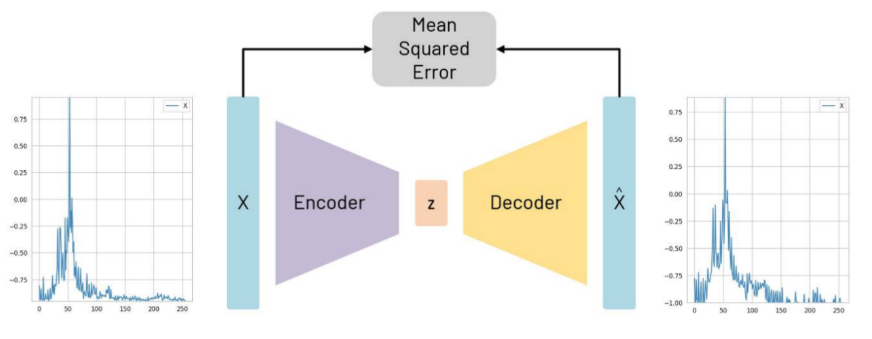

One of ThingIQ’s key AI capabilities is vibration-based anomaly detection, built upon a signal processing and deep learning pipeline designed for industrial IoT environments. Vibration data is acquired in real time from accelerometer sensors and transformed into the frequency domain using the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). Frequency-domain analysis highlights characteristic vibration patterns associated with normal operating conditions of industrial equipment.

After FFT processing and normalization, the data is fed into a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) Autoencoder, where the model learns to reconstruct normal vibration patterns. The reconstruction error is then used as a quantitative metric to detect operational anomalies.

This approach enables the system to:

- Detect subtle deviations before physical thresholds are exceeded

- Adapt to changing operating conditions

- Reduce false alarms compared to traditional rule-based methods

2.1. Vibration Sensor Overview

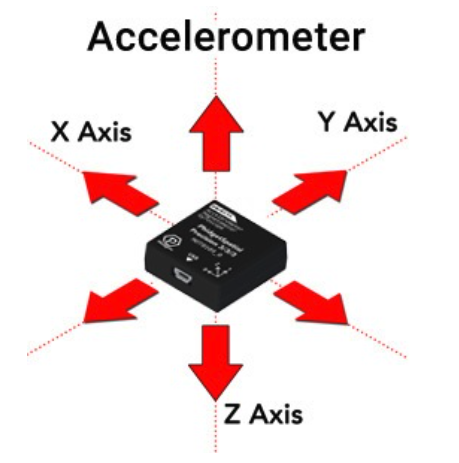

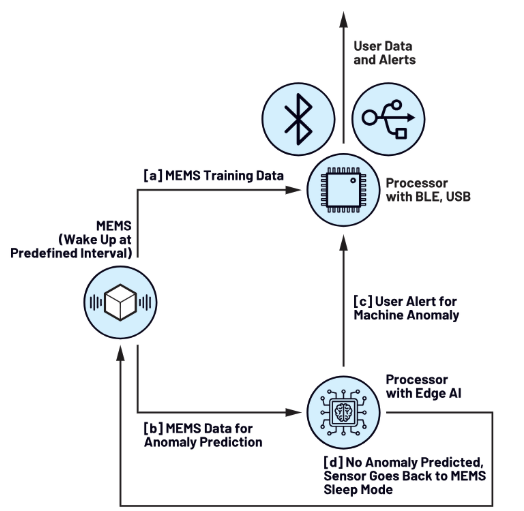

The vibration data is collected using a 3-axis MEMS accelerometer mounted directly on the mechanical structure under monitoring

The sensor measures linear acceleration along three orthogonal axes:

- X-axis: Typically aligned with the horizontal direction

- Y-axis: Typically aligned with the vertical direction

- Z-axis: Typically aligned with the axial or radial direction of the rotating shaft

Figure 1: Accelerometers Measure Acceleration in 3 Axe

2.2. Signal sampling

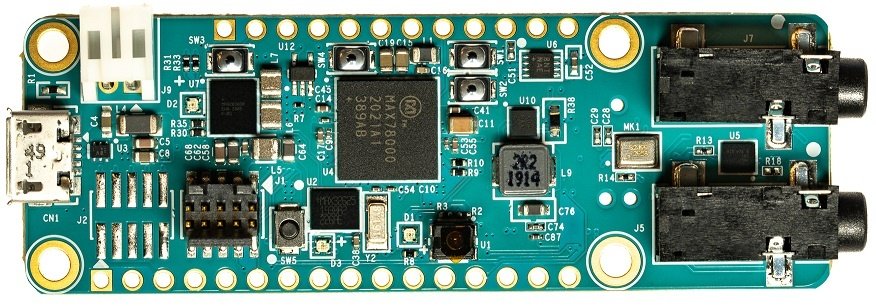

Each axis of the accelerometer produces an analog vibration signal, which is digitized using the MAX78000 ADC.

Typical sampling parameters:

- Sampling frequency (Fs): 20 kHz – 50 kHz

- ADC resolution: 12 bits

- Anti-aliasing filter: Analog low-pass filter applied before the ADC input

The sampling frequency is selected according to the Nyquist rule to ensure that all fault-related vibration frequencies are captured without aliasing.

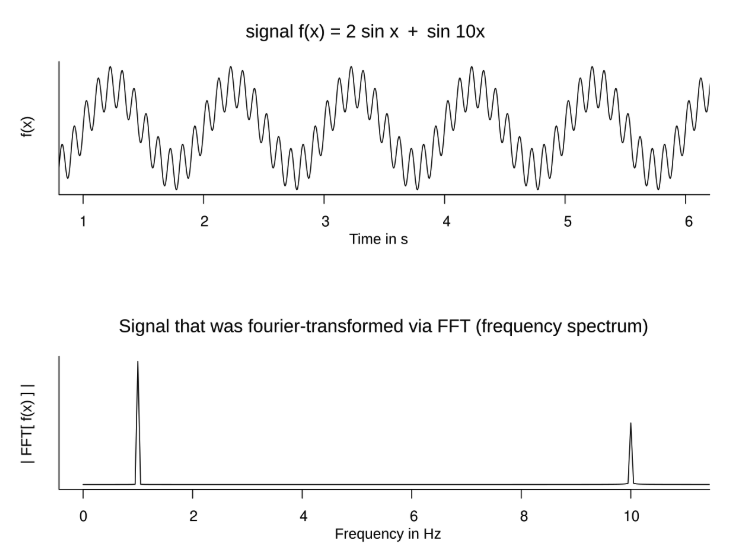

2.3. FFT – Based Feature Extraction

After sampling, the vibration signals from each axis (X, Y, and Z) are transformed from the time domain into the frequency domain using the FFT. Each axis is processed independently.

The FFT converts raw vibration signals into frequency bins, where mechanical faults typically appear as distinct spectral components. Only the magnitude of the FFT is used, as phase information is not required for vibration-based fault detection.

This frequency-domain representation provides compact and informative features that are well suited for predictive maintenance and subsequent AI-based analysis.

3. AI Model Architecture

3.1. Model Tensor Description

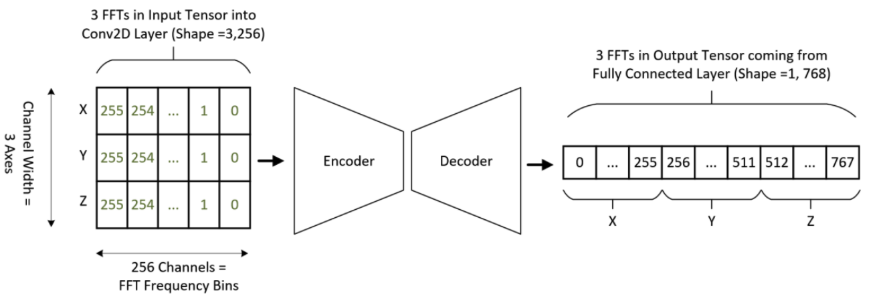

Technical Description of Model Input and Output:

- Model Input Shape: [256, 3] (representing [Signal_Length, N_Channels]).

- Input Details: The input consists of 3 axes (X, Y, and Z), where each axis contains 256 frequency bins (FFT data points).

- Model Output Shape: [768, 1].

- Output Details: The final layer is a Linear layer that produces a flattened output of 768 features (calculated as 256 3).

Figure 2: Autoencoder structure, with reconstruction of an example X axis FFT shown

3.2. Training

Figure 3: Input and output tensor shapes and expected location of data

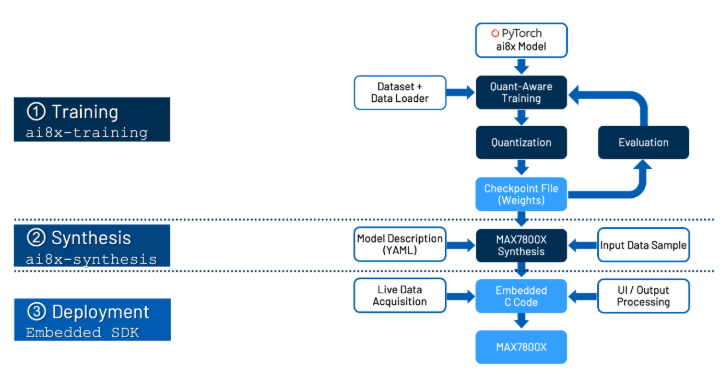

In general, a model is first created on a host PC using conventional toolsets like PyTorch and TensorFlow. This model requires training data that must be saved by the targeted device and transferred to the PC. One subsection of the input becomes the training set and is specifically used for training the model. A further subsection becomes a validation set, which is used to observe how the loss function (a measure of the performance of the network) changes during training.

Depending on the type of model used, different types and amounts of data may be required. If you are looking to characterize specific motor faults, the model you are training will require labeled data outlining the vibrations present when the different faults are present in addition to healthy vibration data where no fault is present.

As a result of this process, three files are generated:

- cnn.h and cnn.c

These two files contain the CNN configuration, register writes, and helper functions required to initialize and run the model on the MAX78000 CNN accelerator. - weights.h

This file contains the trained and quantized neural network weights.

4. Deployment on MAX78000

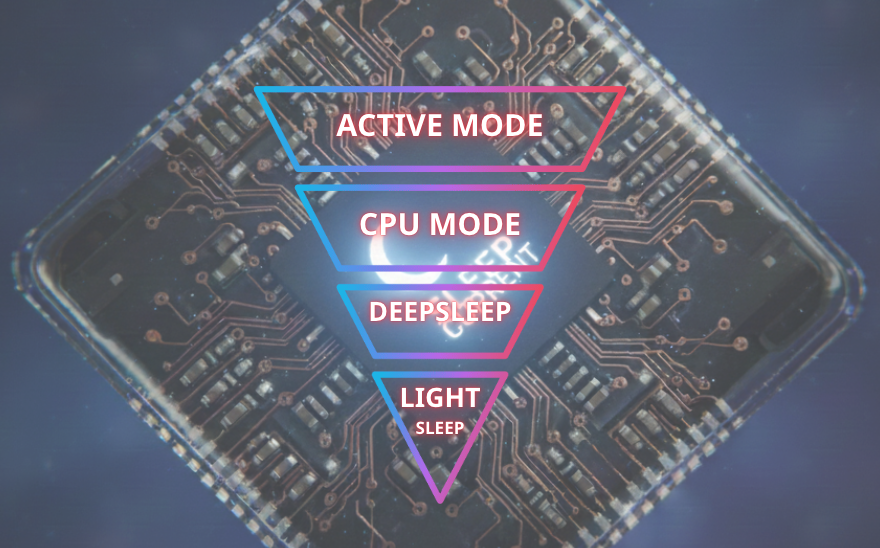

Figure 5: mode of operation

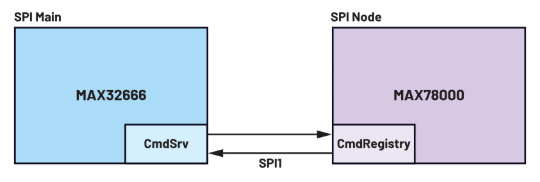

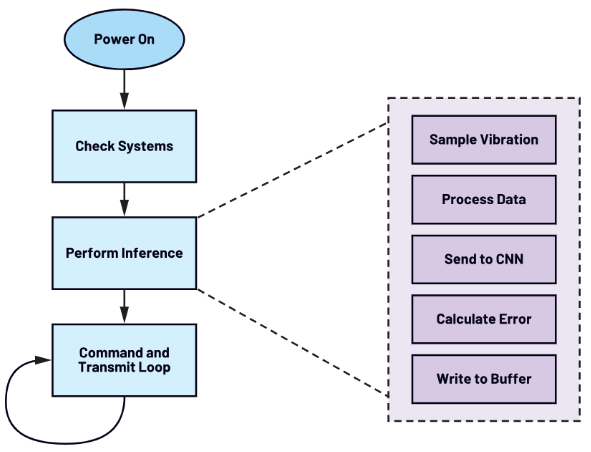

Once the new firmware is deployed, the AI microcontroller operates as a finite state machine, accepting and reacting to commands from the BLE controller over SPI.

When an inference is requested, the AI microcontroller wakes and requests data from the accelerometer. Importantly, it then performs the same preprocessing steps to the time series data as used in the training. Finally, the output of this preprocessing is fed to the deployed neural network, which can report a classification.

Figure 6: AI inference state machine

5. Conclusion

By integrating advanced signal processing techniques with deep learning, ThingIQ provides a robust and scalable approach to vibration-based anomaly detection for industrial IoT systems. The combination of FFT-based feature extraction, CNN autoencoder modeling, Quantization Aware Training, and edge AI deployment enables early detection of abnormal behavior with low latency and high energy efficiency.

This architecture allows enterprises to move beyond reactive, threshold-based monitoring toward proactive, data-driven operations, establishing a solid foundation for predictive maintenance and intelligent asset management in large-scale IoT environments.

ThingIQ – A comprehensive IoT platform

1. What is ThingIQ?

2. IoT platform ThingIQ

3. Integrate AI with ThingIQ

4. Conclusion

1. What is about ThingIQ?

“UPGRADE YOUR IOT FUTURE”

Market tendency – Insight – Action

Over the past decade, the Internet of Things (IoT) has undergone rapid development, from simple monitoring systems to infrastructures connecting millions of devices. However, as IoT matures, the core challenge is no longer data collection, but the ability to transform that data into tangible operational value.

The explosion of sensor data, real-time data, and complex data streams has rendered traditional management models ineffective. In this context, integrating artificial intelligence (AI) into IoT platforms is no longer a trend, but a necessary market requirement.

Faced with this reality, ThingIQ defines its vision: to build an IoT platform that not only connects devices but also supports businesses in making intelligent decisions based on data and AI. Instead of focusing on purely displaying data, ThingIQ’s vision is to bridge the gap between operational data and action, where analytical models and machine learning play a central role in anomaly detection, trend prediction, and system performance optimization. Therefore, the ThingIQ platform is conceived as an AI-integrated IoT solution right from the architectural design stage. Instead of building a connected system and then adding AI later, ThingIQ is developed with an AI-first philosophy, where IoT data is processed, analyzed, and continuously learned to generate actionable insights.

ThingIQ is geared towards large-scale IoT systems where stability, scalability, and integration with existing infrastructure are essential. Based on this vision, ThingIQ is built with a clear layered architecture, enabling real-time collection, processing, and analysis of IoT data, while integrating AI models to support intelligent operation.

2. IoT platform ThingIQ

As IoT systems expand from the experimental stage to real-world deployment, businesses quickly face systemic challenges. These pain points don’t stem from individual devices, but rather from management, operation, the environment, and integration capabilities across the entire IoT infrastructure.

ThingIQ is built to directly address these issues through three core solution groups:

- Intelligent Management & Operations;

- Environmental & Security Solutions;

- IoT Connectivity & API Integration.

For businesses operating hundreds to thousands of dispersed assets such as vehicle fleets, machinery, and industrial equipment, data often comes from multiple sources and protocols, lacking standardization and difficult to utilize effectively. Manual monitoring leads to slow response times, reactive maintenance, and uncontrollable costs. ThingIQ addresses this problem with its intelligent Management & Operations platform, enabling real-time fleet monitoring (GPS, speed, fuel level, engine status via OBD-II and LTE SIM) as well as continuous monitoring of industrial equipment. Data is standardized and processed on an IoT cloud platform, enabling businesses to remotely monitor, analyze operating behavior, support predictive maintenance, and improve asset utilization efficiency.

Devices Management interface ThingIQ

In environments such as smart buildings, factories, and cold storage facilities, a lack of real-time environmental monitoring can lead to significant risks to quality, safety, and energy waste. Temperature, humidity, and energy consumption data are often fragmented, making it difficult for businesses to meet increasingly stringent standards. ThingIQ provides a comprehensive building, energy, and environmental management solution that enables real-time data monitoring and analysis, operational automation, and threshold alerts. This allows businesses to ensure compliance, protect product quality, reduce risks, and move towards sustainable operations at optimal cost.

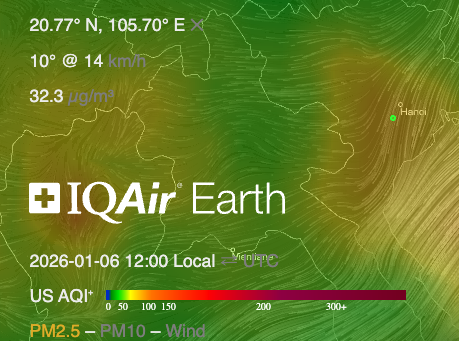

In recent years, air quality in Hanoi has consistently been poor, especially during transitional seasons and peak traffic times, with concentrations of fine particulate matter and air pollutants exceeding recommended levels. This situation not only affects public health but also directly impacts labor productivity and the quality of life. ThingIQ’s IoT-based air quality monitoring solution allows for continuous real-time tracking of pollution indicators, CO₂, humidity, and temperature, enabling businesses, urban areas, and management agencies to proactively assess risks, issue early warnings, and implement timely and effective environmental improvement measures.

Air quality in Hanoi at the beginning of 2026

One of the biggest challenges for enterprise IoT is the fragmentation of devices, protocols, and systems, which isolates data and makes integration with existing platforms like ERP, MES, or BI difficult. ThingIQ addresses this problem through its IoT API Gateway – a secure and scalable middleware that bridges devices, cloud platforms, and enterprise applications. The gateway supports protocol conversion, centralized device management, and real-time data exchange, enabling businesses to seamlessly integrate IoT ecosystems, maintain openness and scalability, and ensure long-term data security.

3. AI in ThingIQ

ThingIQ integrates AI as a foundational component in its IoT architecture, transforming multi-source sensor and operational data into exploitable knowledge. Machine learning models are deployed directly in the data processing pipeline, allowing the system to learn from the real-world operating behavior of devices and the environment, rather than relying on thresholds or static rules.

The AI in ThingIQ focuses on core analytical problems of enterprise IoT, including contextual anomaly detection, trend analysis, and device state prediction. Through learning from historical and real-time data, the platform supports predictive maintenance, reduces unplanned downtime, and optimizes asset lifecycles.

ThingIQ’s approach aims for AI that is controllable and explainable, ensuring compliance with operational requirements and data security. AI not only serves for display purposes, but also acts as a decision support layer, helping businesses shift from passive monitoring to proactive, data-driven operations.

For example, when comparing two systems, one with AI integration and one without, the advantages of AI applications become clear:

- For IoT systems without AI: Traditional systems are primarily based on data collection and fixed thresholds. Sensors send data (temperature, humidity, equipment status) to a central platform, where the data is displayed on a dashboard and triggers alerts when predefined thresholds are exceeded. This approach is suitable for basic monitoring but is limited in complex operating environments where operating conditions change constantly. The system only reacts after an incident has occurred, easily leading to false alarms and making it difficult to support optimal operation or proactive maintenance.

- Case 2: IoT systems with AI (ThingIQ) are integrated into the ThingIQ platform. IoT data is not only monitored but also analyzed contextually. Machine learning models study the normal operating behavior of equipment and the environment, thereby detecting anomalies early even before values exceed thresholds. AI allows for forecasting trends and equipment status, supporting predictive maintenance and operational optimization. Instead of reacting passively, businesses can proactively make decisions based on data and forecasts.

From there, we get a comparison table to better understand the AI features:

4. Conclusion

In the short term, ThingIQ focuses on developing and deploying comprehensive IoT solutions, helping businesses quickly solve real-world operational challenges, optimize asset, environmental, and system management, while ensuring flexible and stable deployment.

In the long term, ThingIQ aims to build an AI-integrated IoT platform as the core data infrastructure for businesses, where data is analyzed in depth to support intelligent decision-making, operational automation, and sustainable growth.

In terms of expertise and commitment, the ThingIQ team possesses comprehensive capabilities ranging from hardware design and development, IoT connectivity system deployment, to cloud integration and operation. By leveraging advanced connectivity protocols and in-depth data analysis, we deliver smarter, more efficient, and future-ready industrial solutions.

ThingIQ is committed to quality, innovation, and customer satisfaction at every stage, from design and implementation to system operation and scaling!

Sleep Current of XIAO nRF52840

1. Introduction

2. Sleep current in practice

2.1. Measuring tool

2.2. Understanding sleep currents correctly

3. Conclusion

1. Introduction

In IoT systems and battery-powered devices, microcontrollers spend most of their time in a dormant state, so sleep current – the current consumed when the system is “sleeping” – often has a much greater impact than the current consumed when operating. Especially with applications like BLE beacons, sensor nodes, or wearables, devices can sleep for over 99% of their operating time, meaning even a few microampere differences in sleep current can significantly alter battery life from a few months to several years. Nordic Semiconductor’s nRF52840 is known as a BLE SoC with very low power consumption, with sleep current values in the microampere range as stated in its datasheet. However, in practice, many projects have reported much higher current consumption than expected, even reaching hundreds of microampere or several milliampere values despite the firmware putting the system to sleep. The main reason is that CPU-level sleep is not synonymous with system-level sleep: clocks, peripherals, BLE radios, GPIOs, or external hardware components can still run in the background and continuously wake the SoC. Furthermore, datasheets often reflect ideal measurement conditions, while the actual system is a combination of firmware, BLE configuration, hardware, and measurement methods. This article aims to clarify the nature of sleep current on the nRF52840, highlight the differences between theory and actual measurements, and provide a systematic approach to analyzing, measuring, and optimizing current consumption down to the microampere level in practical applications.

2. Sleep current in practice

2.1. Measuring tools

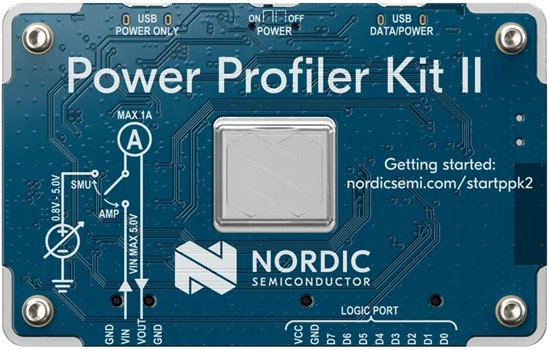

Nordic Semiconductor’s Power Profiler Kit II (PPK2) is an affordable hardware and software tool that helps engineers flexibly measure power consumption for IoT devices, especially with the Nordic nRF chip, allowing simultaneous viewing of both average and high-current event data with a faster sampling rate (100ksps), integrated via the nRF Connect application on a PC for more efficient energy analysis and optimization.

The Power Profiler Kit II (PPK2) is a specialized power consumption measurement tool developed by Nordic Semiconductor, designed for energy analysis and optimization in low-power embedded systems. This device provides high-accuracy current measurement capabilities, particularly suitable for battery-powered IoT applications.

Key features of the PPK2 include:

- Flexible current measurement, supporting both average current and peak current modes, allowing for detailed analysis of system power consumption behavior.

- High sampling rate, up to 100 kSamples/s, approximately 10 times faster than the previous generation, enabling clear observation of very short power consumption events such as radio on/off, wake-up, or interrupt handling.

- The included software, integrated into the nRF Connect for Desktop Power Profiler application, allows for visual real-time display of measurement data and supports data export for further analysis.

- A 10-pin logic interface allows monitoring logic signals from the test device (DUT) synchronized with current consumption data, useful for linking firmware behavior to current spikes during energy optimization.

- The PPK2 has a wide range of applications, particularly effective in optimizing energy consumption for BLE, LTE-M, and NB-IoT devices, and is often used with development kits such as the nRF9160.

The basic operating principle of the PPK2 is quite simple: the device is connected to a computer via a Micro-USB cable and to the DUT using jumper wires to both power and measure current consumption. Users utilize the nRF Connect Power Profiler application on their PC to configure the measurement mode, observe the current graph over time, and thus detect periods of high or low energy consumption in the system’s operating cycle.

The target users of the PPK2 are primarily hardware and software engineers developing battery-powered IoT products, as well as those who need to analyze and optimize battery life for low-power applications where every microampere counts.

2.2. Understanding sleep currents correctly

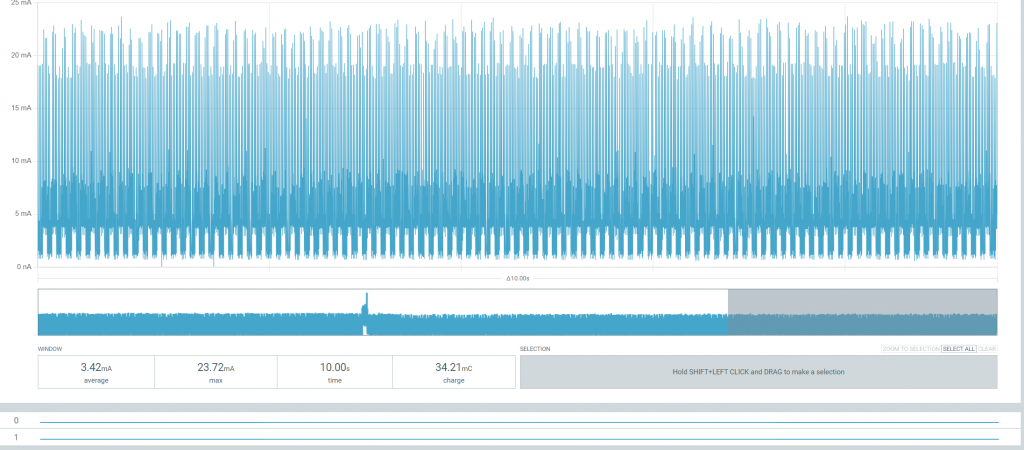

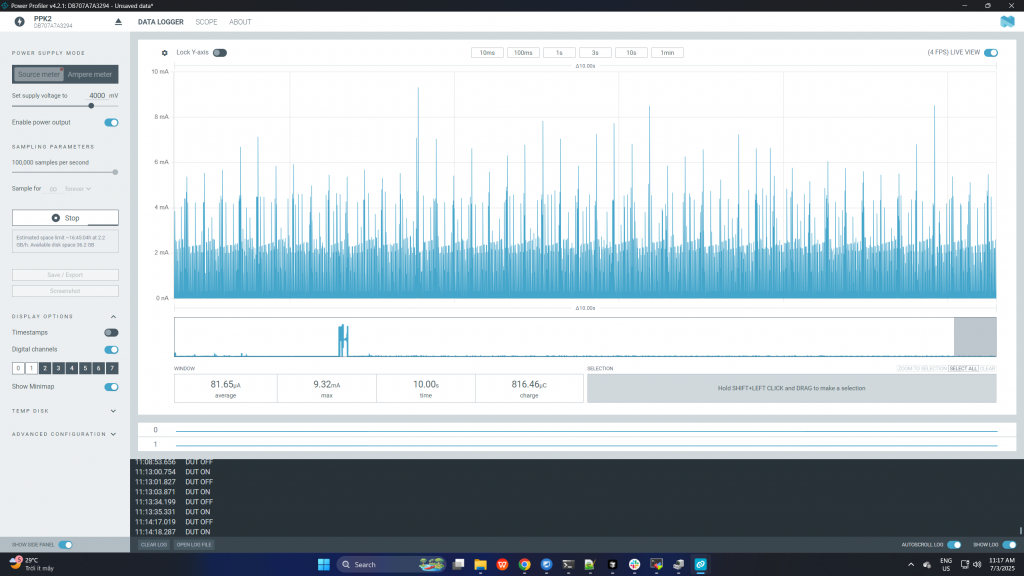

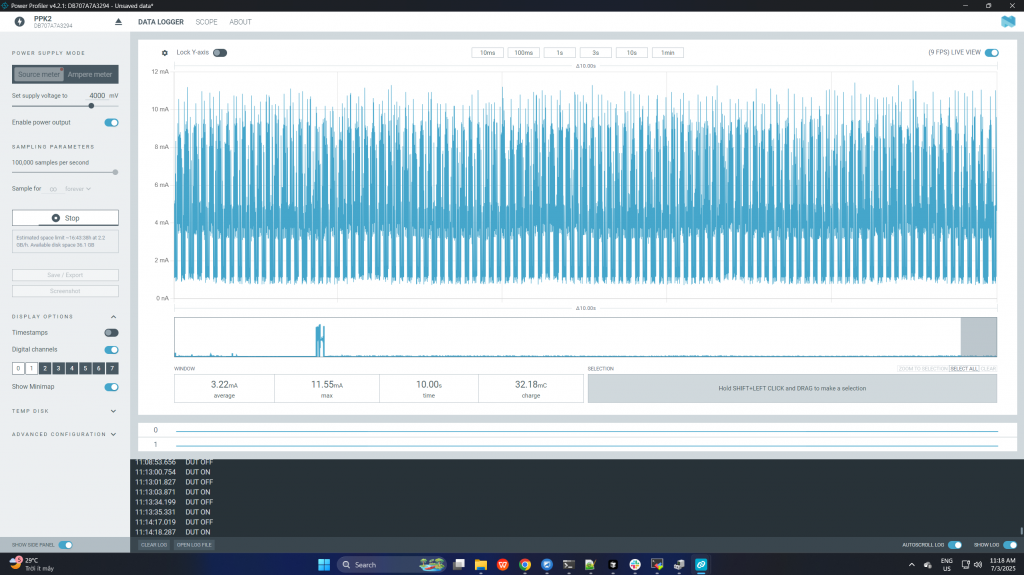

To clarify the information related to Sleep Current, we measured the nRF52840 using the Nordic Power Profiler Kit II (PPK2) at a sampling rate of 100 kS/s over a period of 10 seconds, yielding the following results:

Overall view: “The device is not really sleeping”

Observation shows that the current fluctuates continuously from ~0 mA to ~20+ mA, with no “flat” segment at the µA level; the pulse density is high, uniform, and repeats periodically. This is not true sleep, but rather a CPU sleep mode while the radio/clock/background tasks are still running. This indicates that the device is being woken up periodically; even though the firmware has invoked sleep, the current consumption still varies significantly with mA‑level spikes. This proves that ‘sleep’ at the CPU level does not equate to low power at the system level.

For this case, the “thought it was sleeping” case: the average is low but the underlying behavior is still wrong. It’s easy to see that the measured parameters include: average current: ~81.65 µA, peak: ~9.32 mA, Measurement time: 10 s, charge: ~816 µC. Next, looking at the waveform, the baseline is quite low (µA–tens of µA) but there are still mA-level spikes appearing continuously and there is no stable flat-line segment. The device has not really entered a proper System ON low-power mode; the BLE radio or timer is still active, and the sleep current does not reach the datasheet level. Although the average current is only about 80 µA, the waveform shows that the device is still generating periodic mA-level spikes. This is a common mistake: evaluating sleep current only based on the average value while ignoring the actual behavior of the system.

Finally, let’s look at this figure: the Active / BLE-heavy state (reference) with parameters: average: ~3.22 mA, peak: ~11.55 mA, charge: ~32.18 mC / 10 s. This corresponds to a state of dense BLE advertising or a short BLE connection interval, where the CPU + radio are operating frequently, showing the current consumption when the device is actively running. Notably, the waveform of the “non-optimized sleep” state (previous picture) has a shape very similar to this active state.

3. Conclusion

Sleep current is often treated as a single number quoted from a datasheet, but practical measurements on the nRF52840 show that it is a system-level characteristic, not merely a CPU state. Through real measurements using the Nordic Power Profiler Kit II (PPK2), this article demonstrates that a device can appear to be “sleeping” at the firmware level while still consuming significant energy due to periodic wake-ups, active clocks, BLE radio activity, or misconfigured peripherals.

The measurement results clearly show three distinct behaviors: a fully active BLE-heavy state with continuous milliampere-level current, a misleading “average-low-current” state where the baseline is low but frequent mA-level spikes persist, and a properly optimized sleep configuration where the system finally approaches the microampere-level currents stated in the datasheet. This highlights a common pitfall in low-power design: relying solely on average current values without examining the actual current waveform can lead to incorrect conclusions about battery life.

Using a high-resolution measurement tool such as PPK2 is therefore essential. Its high sampling rate makes short current spikes visible, enabling engineers to correlate power consumption with firmware behavior and identify hidden wake-up sources. Only by analyzing both the shape of the current waveform and the statistical values (average, peak, and charge) can true low-power operation be verified.

In conclusion, achieving datasheet-level sleep current on the nRF52840 requires a holistic approach that combines correct firmware sleep states, careful BLE configuration, proper clock and peripheral management, and clean hardware design. When these factors are addressed together—and validated with accurate measurement tools—microampere-level sleep current is not only theoretical but achievable in real-world IoT applications.

Microphone & Audio Processing Pipeline in nRF52840

1. Introduction

1.1. Introduce about nRF52840

1.2. Analog microphone vs PDM microphone

2. Mono and Stereo hardware

2.1. Mono mode

2.2. Stereo mode

3. Data processing stream

4. Conclusion

1. Introduction

1.1 Introduce about nRF52840

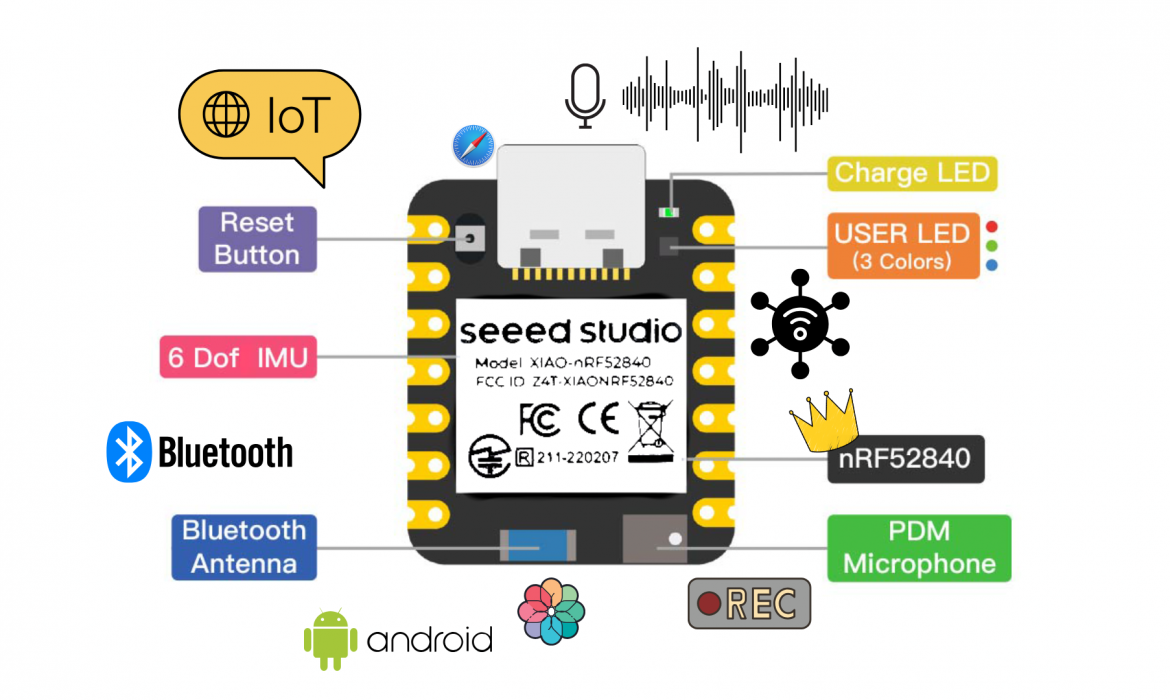

Seeed Studio XIAO nRF52840 is the first wireless board in the XIAO series, featuring the Nordic nRF52840 SoC with Bluetooth Low Energy 5.0 support. Its ultra-compact form factor, single-sided SMD design, and integrated Bluetooth antenna make it well-suited for mobile devices and rapid IoT prototyping.

The XIAO nRF52840 Sense variant integrates a digital PDM microphone and a 6-axis IMU, enabling real-time audio capture and motion sensing. These onboard sensors make it ideal for TinyML applications such as voice recognition, acoustic event detection, and gesture recognition. The upgraded XIAO nRF52840 Plus and Sense Plus versions further enhance usability by increasing the number of multifunctional pins to 20, adding I2S and SPI resources, exposing NFC pins, and optimizing the BAT pin placement for easier soldering and power integration. The board provides rich interfaces including UART, I2C, and SPI, with 11 digital (PWM) pins and 6 analog (ADC) pins, along with 2 MB of onboard flash memory. It supports multiple development environments such as Arduino, MicroPython, CircuitPython, and Zephyr SDK.

Typical Applications:

- Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE): low-power IoT devices, beacons, wearables, sensor data streaming

- Voice & Audio Processing: audio capture, voice recognition, keyword spotting

- Recorder: local audio recording or BLE audio transmission

- TinyML: gesture recognition, audio classification, edge AI

1.2. Analog microphone vs PDM microphone

In the nRF52840, both analog microphones and PDM (Pulse Density Modulation) microphones can be used. However, PDM microphones are generally preferred for high-quality digital audio applications such as audio-based machine learning. While analog microphones require an external ADC for signal digitization, PDM microphones output digital data directly. This allows tighter integration with the MCU, higher overall performance, improved noise immunity, and reduced GPIO usage—especially when using advanced PDM drivers provided by mbed OS or the Nordic SDK.

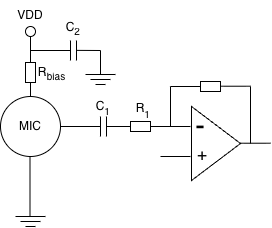

For analog microphones, to better understand their operating principle, we consider a typical circuit based on an electret microphone with a simple yet effective signal amplification structure. The electret microphone is powered through a bias resistor Rbias (typically in the range of 2.2 kΩ to 10 kΩ) connected from VDD to the signal pin. This biasing provides the correct operating conditions for the internal FET transistor inside the microphone.

The microphone produces an AC audio signal, which is separated from the DC component by a coupling capacitor C₁ before being fed into the op-amp input. At this stage, resistor R₁ sets the input impedance and, together with the op-amp, forms an amplification stage. Meanwhile, the VDD supply is stabilized using a bypass capacitor to reduce power-supply noise and prevent it from affecting the output signal.

With this configuration, the audio signal captured from the microphone is amplified in a stable manner, exhibits reduced noise, and achieves sufficient quality for further processing or digitization in subsequent stages. The overall circuit can be modeled as follows:

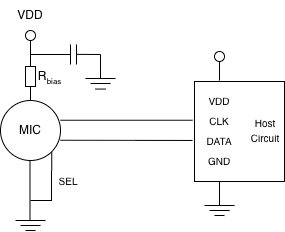

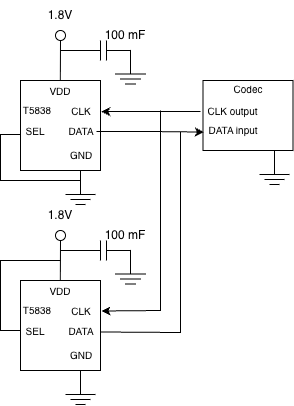

Diagram Analog microphone

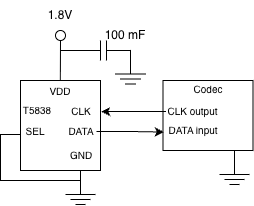

For PDM microphones, the operation follows the principle of digital pulse density modulation. The PDM microphone is powered via the VDD pin and connected to ground at the GND pin. Once the acoustic signal is captured, it is directly converted into a PDM bitstream inside the microphone and transmitted to the host circuit through the Data pin. The microphone’s operation and data synchronization are controlled by a Clock signal provided by the host and applied to the Clock pin of the microphone. In addition, the SEL (Select) pin—typically connected to the host circuit—allows selection between the Left or Right channel when multiple microphones share the same PDM bus. If only a single microphone is used, this pin can be fixed to a defined logic level by pulling it up or down through an appropriate resistor. To ensure signal stability and minimize noise, a bypass capacitor is usually placed close to the microphone’s VDD pin to filter power-supply noise. With this configuration, the system achieves stable digital audio capture, where data is streamed directly into the processing block without requiring an intermediate analog amplification stage. The overall structure can be summarized by the following block diagram:

Diagram PDM microphone

The choice of using MEMS microphones with analog or digital output signals often depends on how the output signal will be used. Analog output signals are convenient if they are connected to an amplifier input for analog processing in the host system. Examples of common analog applications are simple loudspeakers or radio communication systems. MEMS microphones with analog outputs also tend to consume less power than microphones with digital outputs due to the absence of an ADC converter.

2. Mono and Stereo hardware

Based on the operating principle of PDM microphones, the audio signal is already digitized inside the microphone and streamed directly to the microcontroller via the PDM interface. This significantly simplifies the analog front-end and enables flexible microphone configurations. On the nRF52840 platform, the dedicated PDM hardware peripheral supports both mono and stereo microphone setups, making it suitable for a wide range of applications such as voice recognition, audio recording, and spatial audio processing. The following section describes in detail the hardware configurations for mono and stereo PDM microphones.

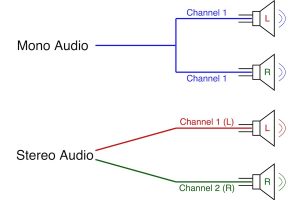

Mono mode vs Stereo mode

2.1. Mono mode

Connect Mono with Codec

Mono (Monophonic) is an audio effect where sound is captured and played from a single source. Because it comes from a single source, it can be difficult to distinguish the location of the sound in space.

Fieldy firmware supports mono mode via both software and hardware:

- For hardware: Fieldy uses only one PDM microphone; the SEL pin of the microphone is fixed because it only uses one channel, and the MCY only reads one DATA stream.

- The microphone connects directly to the nRF52840’s PDM peripheral; it does not use an ADC or an external audio codec for recording.

Configuration of samples rate suitable voice:

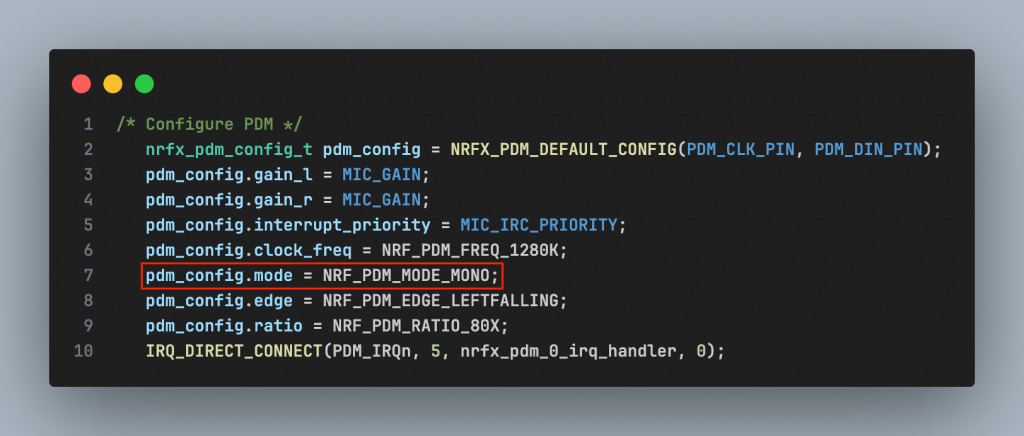

Configuration of PDM in Mono mode

In the driver microphone (mic.c):

mic.c settings

Calculate from here frequency for mono PCM is 16 KHz The suffer PCM 1 channel:

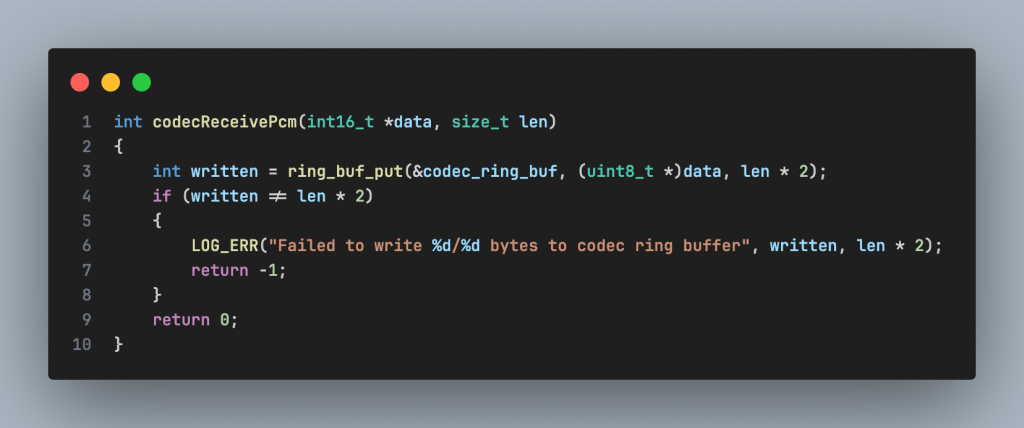

Besides, supporting mono mode in codec:

Opus encoder mono

No parameter for channel, PCM default is mono:

Codec API support only mono mode

Next, Fieldy firmware supporting in configuration the systems in this file config:

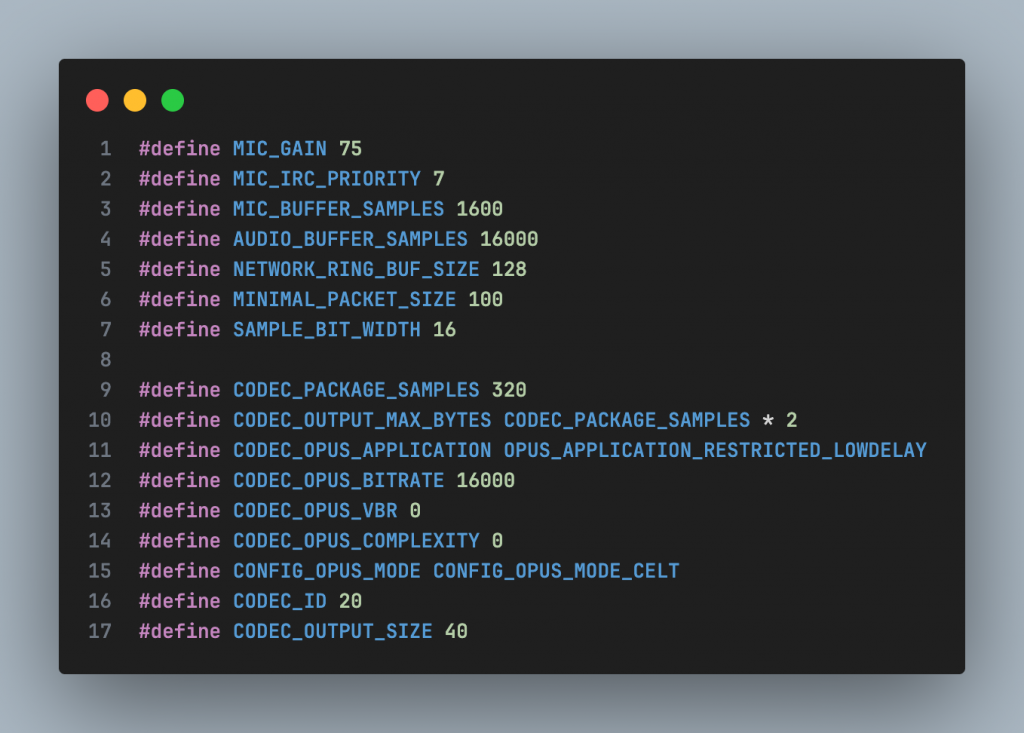

Configuration audio system

The audio system is configured for single-channel (mono) voice capture and encoding with a sampling frequency of 16 kHz. 16-bit PCM data is packed into 20 ms frames and compressed using the Opus codec in CELT mode, with a fixed bitrate of 16 kbps, to optimize low latency, low power consumption, and suitability for data transmission over BLE.

2.2. Stereo mode

Stereo sound is audio that is reproduced from two separate sound channels, played through a speaker system with a two-speaker configuration, or through headphones, allowing the listener to perceive the spatial position of sounds. Stereo sound is associated with spatial positioning through the variation of sound between the two component speakers, helping to distinguish left/right sound positions effectively.

Stereo mode

The nRF52840 MCU supports stereo audio recording via the PDM peripheral. However, in 6 the current Fieldy hardware design, only one PDM microphone is used and it is configured in mono mode. To implement stereo mode, a second microphone needs to be added or a stereo PDM microphone used (with integrated …), and the PDM peripheral and Opus codec must be reconfigured for two-channel operation.

3. Data processing stream

Data stream in single channel mode maybe set a diagram like:

Diagram of structure firmware

- PDM MIC: encode analog signals (Raw audio signals have frequencies 1-3MHz) into digital signal. nRF52840 PDM HW: PDM hardware in MCU; receive DATA, eliminate interference CIC, decrease frequency (decimation), finally export file .pcm.

- Before reaching the buffer, the signal is pulse-code modulated (converting the audio signal into a digital signal).

- Audio Buffer/DMA: The buffer help to improve the output signal, increase quality, decrease interference and output impedance,…

- Opus Encoder: Audio signal is compressed down to low bitrate, keep the quality of voice.

- BLE/Storage/RF: Finally, the signal is taken to perform the system’s required operations such

as transmission, storage, amplification, etc.

4. Conclusion

The nRF52840 is a capable and energy-efficient microcontroller platform for low-power audio applications. By leveraging PDM microphones and software-based audio processing, the system can operate reliably with a current consumption of approximately 2–3 mA at 3.8 V, making it well suited for battery-powered devices such as wearables, IoT nodes, and portable audio recorders.

However, due to the lack of a hardware audio codec, all audio encoding and decoding tasks (e.g., Opus) must be handled in software by the CPU. This results in lower processing efficiency compared to systems equipped with dedicated hardware codecs. Furthermore, the absence of a dedicated DSP unit means that digital signal processing tasks such as filtering, compression, and encoding consume additional CPU cycles, RAM, and power.

Overall, the nRF52840 is well suited for low-complexity to moderate audio workloads where power efficiency and flexibility are prioritized. For applications requiring high-performance, real-time audio processing, SoCs with integrated DSPs or hardware audio codecs may offer more optimal solutions.

Analyzing Bluetooth Low Energy Data Transfer Speed Across PHY Modes with an IoT Demo

1. Introduction to Bluetooth Low Energy Data Transfer Speed

2. Speed in PHY modes

3. BLE Data Transfer Speed Demo Using an IoT Project

4. Conclusion and Futute Improvements for BLE Data Transfer

1. Introduction to Bluetooth Low Energy Data Transfer Speed

Welcome to Industrial Embedded Solutions – where we deliver modern, reliable, and optimized industrial embedded solutions for real-world challenges in manufacturing, IoT, and automation. With a team of experienced engineers, we focus on transforming complex technologies into efficient, easy-to-deploy, and scalable solutions.

In this content, we introduce the topic of BLE speed (Bluetooth Low Energy) – a critical factor when designing low-power wireless communication systems. You will explore the factors that affect BLE data throughput, the practical limitations compared to theoretical values, and effective ways to optimize configurations to achieve the best performance for industrial embedded applications.

In Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE), the term ”speed” refers to the normal data rate at the physicals (PHY) layer, representing the number of bits that can be transmitted over the wireless channel per second. According to the BLE 5.x specification, common PHY modes include 1M PHY with a data rate of 1Mbps anh 2M PHY with a data rate of 2 Mbps. These values are theoretical anh do not directly represent the mount of useful data received by the application, as protocol overhead from higher layers such as the Link Layer and ATT/GATT is still present. Therefore, BLE speed is primarily used to describe the transmission capability of the standard and hardware, while actual data transmission performance should be evaluated using throughput.

2. Bluetooth Low Energy Speed Across PHY Modes

BLE (Bluetooth Low Energy) speeds typically reach a maximum of 1-2 Mbps (Megabits per second) depending on the version, but actual throughput is lower (around 305 kbps) due to optimization for energy saving, sending short data streams, and frequent pauses between transmissions, unlike Bluetooth Classic (1-3 Mbps) used for continuous transmission such as audio. BLE versions 5.0 and above can achieve 2 Mbps (high speed) or decrease to 125/500 kbps (long range), but the main purpose remains low power consumption. BLE: Lower speed, optimized for energy saving, suitable for sensors, wearable devices (IoT), and small data transmission.

For 1M BLE, the speed is 1 Megabit/second (Mbps). This is the most basic and common PHY physical layer, supported by all BLE devices, operating at 1 Megasymbol/second (Msym/s). Although the theoretical speed is 1 Mbps, actual throughput is often lower (around 305 kbps) due to factors such as encoding and overhead, but it offers a good balance between power saving and operating range for everyday applications. This is the standard and backward-compatible PHY mode; all Bluetooth LE devices must support it. It’s suitable for transmitting small data such as sensor status and notifications, as it optimizes power. When two BLE devices connect, they start in 1M PHY mode, then can switch to faster modes if both support it (e.g., LE 2M PHY).

For 2M BLE, the speed is 2 Megabits per second (2 Mbps), introduced in Bluetooth 5.0, doubling the speed of 1M PHY BLE, allowing for faster data transmission or reduced transmission times to save energy, but comes with a shorter range due to the higher speed. 2Mbps BLE is designed to increase data transmission speed on the PHY (Physical Layer). This doubles the amount of bits transmitted in the same amount of time, reducing transmission time and thus reducing energy consumption for the same amount of data. However, the system has to compromise on speed, potentially increasing the bit error rate and resulting in a narrower connection range (approximately 80% compared to 1Mbps PHY). 2Mbps BLE is suitable for IoT applications requiring fast but not excessively large data transmission, such as temperature and humidity sensors. Comparison with other BLE speeds 1Mbps BLE PHY 1 Mbps (base speed, wider range):

• Coded PHY (S=2): 500 Kbps (the speed is lower but the scale is farther).

• Coded PHY (S=8): 125 Kbps (the worst speed, the furthest scale).

The speed of BLE Coded (Bluetooth LE Coded) in Bluetooth 5.x depends on the encoding mode, offering two main speeds to prioritize range over high speed: 125 kbps (S=8) and 500 kbps (S=2), using a Forward Encoding Scheme (FEC) to increase stability and range (up to 1000m under ideal conditions), much lower than the 1 Mbps or 2 Mbps speeds of uncoded PHYs. When connecting devices over very long distances (e.g., IoT devices in smart homes, industrial sensors), using BLE Coded becomes optimal, where stability and coverage are more important than fast data transmission speed. In short, BLE Coded is a trade-off in Bluetooth 5.0+ for speed, allowing for more robust connections over long distances.

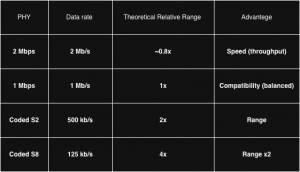

From this, we can summarize the speed, throughput, and other factors of the different BLE variants as follows:

Table of compare between the variants of BLE

The symbol rate in BLE defines the number of modulation symbols transmitted per second at the physical layer and is expressed in symbols per second (sym/s). In BLE 1M and 2M PHY modes, Gaussian Frequency Shift Keying (GFSK) modulation is employed, where each symbol represents one bit of information. As a result, the symbol rate is numerically equal to the nominal PHY date rate. Specifically, the 1M PHY operates at a symbol rate of 1 Msym/s, while the 2M PHY operates 2Msym/s. Increasing the symbol rate directly increases the nominal transmission speed; however, it also reduces receiver sensitivity and shortens the effective communication range, making higher symbol rates more susceptible to noise and interference.

3. BLE Data Transfer Speed Demo Using an IoT Project

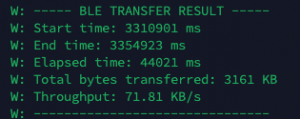

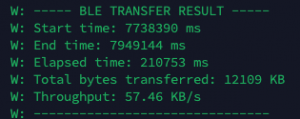

To understand BLE more clearly, we started to create a demo using Bluetooth Low Energy in IoT to record with IoS standard and Android standard. The demo system is built around the Nordic Semi- conductor nRF52840, a BLE 5.0 – capable SoC supporting 1M and 2M PHY, Data Length Extension (DLE) and extended MTU sizes. The nRF52840 operates as a BLE peripheral, while smartphones running iOS and Android act as BLE central devices. On the embedded side, the firmware is developed using the Nordic SDK or Zephyr RTOS BLE stack, which allows fine-grained control over PHY mode, connection parameters, and GATT behavior. On the mobile side, the demo application uses CoreBluetooth on iOS and the Android BLE API on Android to receive data from the peripheral.

The experimental results show a clear performance difference between iOS and Android under identical peripheral configurations. When connected to Android devices, the BLE link achieves significantly higher throughput, approaching the expected performance for a 2M PHY configuration. In contrast, iOS devices exhibit lower throughput despite successfully negotiating the same MTU size and PHY mode. This difference is primarily attributed to platform-level restrictions in iOS, including limited control over connection interval, stricter notification pacing, and conservative scheduling policies designed to optimize power consumption.

Although both of platforms report the same nominal BLE speed at the PHY level, the effective data rate observed on iOS is substantially lower. This demonstrates that BLE speed alone does not determine real world data transfer performance and highlights the importance of throughput based evaluation.

Carry out a survey of throughput on Android

Carry out a survey of throughput on IoS

The results confirm that BLE performance is not solely determined by the peripheral hardware or the BLE specification, but also by the operating system and BLE stack implementation of the central device. Android provides greater flexibility in controlling BLE connection parameters, allowing higher data rates to be achieved. In contrast, iOS abstracts the Link layer and enforces conservative limits to ensure energy efficiency and system stability. These design choices make iOS less suitable for high throughput BLE applications but beneficial for long battery life.

4. Conclusion and Future Improvements for BLE Data Transfer

In conclusion, BLE speed is influenced by many factors beyond the theoretical specifications of Bluetooth Low Energy, including PHY selection, connection interval, packet size, protocol overhead, and the processing capability of the embedded system. While BLE is not designed to compete with high-throughput wireless technologies, it offers an excellent balance between data rate, power consumption, and reliability.

By understanding these limitations and carefully tuning parameters such as MTU size, Data Length Extension, and PHY mode, developers can significantly improve real-world throughput. Ultimately, optimizing BLE speed is not about achieving the maximum possible data rate, but about meeting application requirements efficiently while maintaining low power consumption and stable communication—key priorities in industrial embedded and IoT systems.